By David Lowenstein and Nathaniel Walton, Michigan State University Extension

As the shadows lengthen and days get shorter, we start to see some six-legged friends sneaking around our windows, eaves and soffits. This is a good time for a reminder about just who some of these insects are and how you can tell them apart. The fall invaders are all just following their natural inclination to seek an out-of-the-way resting place to spend the winter. Unfortunately for all parties involved, what happens next is anything but natural. The exterior side walls of our structures provide a very attractive array of nooks and crannies for these critters to sneak into. The problem is that these nooks and crannies often lead into the interiors of our human dwellings.

Who are the insects on the side of my home?

Three of these fall invading species in Michigan are all closely related insects in the order Hemiptera (true bugs). They are the boxelder bug, brown marmorated stink bug and western conifer seed bug (Table 1). It is possible to find all three on the outside of structures in late summer or fall.

Of these three insects, brown marmorated stink bug is the newest arrival to Michigan and the only one that is a garden or agricultural pest, according to Michigan State University Extension. Often confused for a stink bug, western conifer seed bug is less common than brown marmorated stink bug and typically remains unnoticed until fall. Boxelder bug is a native Michigan insect that can be quite abundant in some parts of Michigan in certain years. Boxelder bugs are not garden pests, but they can be a nuisance in homes simply due to the sheer number of them that can accumulate on windowsills and in attics during winter.

In case you are unsure whether the insects in your home are brown marmorated stink bugs, Photo 1 and Table 1 will help tell them apart. The shape of their hind legs, overall body shape and color can be used to differentiate these three fall invaders. Additional information on managing brown marmorated stink bug can be found on the Stop BMSB website.

Like many of the other insects in the order Hemiptera (true bugs), these bugs have a piercing sucking mouthpart and are capable of using it in self-defense. In other words, handle them with caution. None of these insects transmit any disease or sting. They also will not reproduce in the winter. Their presence is restricted to being a nuisance. In severe cases, high numbers of these bugs may stain furniture through external secretions.

A fourth fall invading insect worth mentioning is the multi-colored Asian lady beetle (Photo 2). These beetles spend their summers eating aphids and other pest insects in our crop fields. In the fall, they can form large aggregations on the sides of structures as they look for a place to spend the winter.

Unlike the three insects mentioned previously, multi-colored Asian lady beetles are beetles (Coleoptera), not true bugs. Asian lady beetles can bite but cannot spread disease. They also emit defensive secretions that have a slight odor, can stain fabrics and in rare cases have been known to cause allergic reactions.

What causes these insects to aggregate?

The summer months are a time when insects are active in gardens, trees or shrubs. As daylight lessens, insects undergo a physiological change known as diapause. This is characterized by an extended time of inactivity during which they do not reproduce and eat little or nothing. In their natural habitat, these insects spend winter beneath bark.

Stink bugs begin to aggregate on the sides of buildings and structures when there is less than 12.5 hours of daylight, approximately the second or third week of September in Michigan. South and west facing walls are most susceptible to large populations. They particularly move towards garages, sheds and sidings with small spaces or gaps that are protected from the weather. For several weeks in the fall, stink bugs and other aggregating insects may attempt to enter homes in search of a winter environment protected from moisture and cooler air temperatures.

How can I keep them out of my home?

During fall, search for spots on the outside of the house with gaps that are wide enough for insects to enter. These areas can be covered with wire mesh, screens or caulk. Window air conditioning units should be checked for gaps and covered. When there are hundreds of swarming insects on the outside of a home, leave the windows closed or check for gaps in the screen. A strong force of water can knock insects off exterior walls.

On homes with severe outbreaks, a pyrethroid insecticide can be applied to the foundation or siding. This will only kill insects that contact the insecticide and is not an effective long-term strategy. Since these fall-invading insects can fly up to several miles, it is likely more will return on the next warm day. When smaller numbers are present inside or outside, the insects can be knocked into a bucket of soapy water, vacuumed up or just left alone.

What can I do once they get inside?

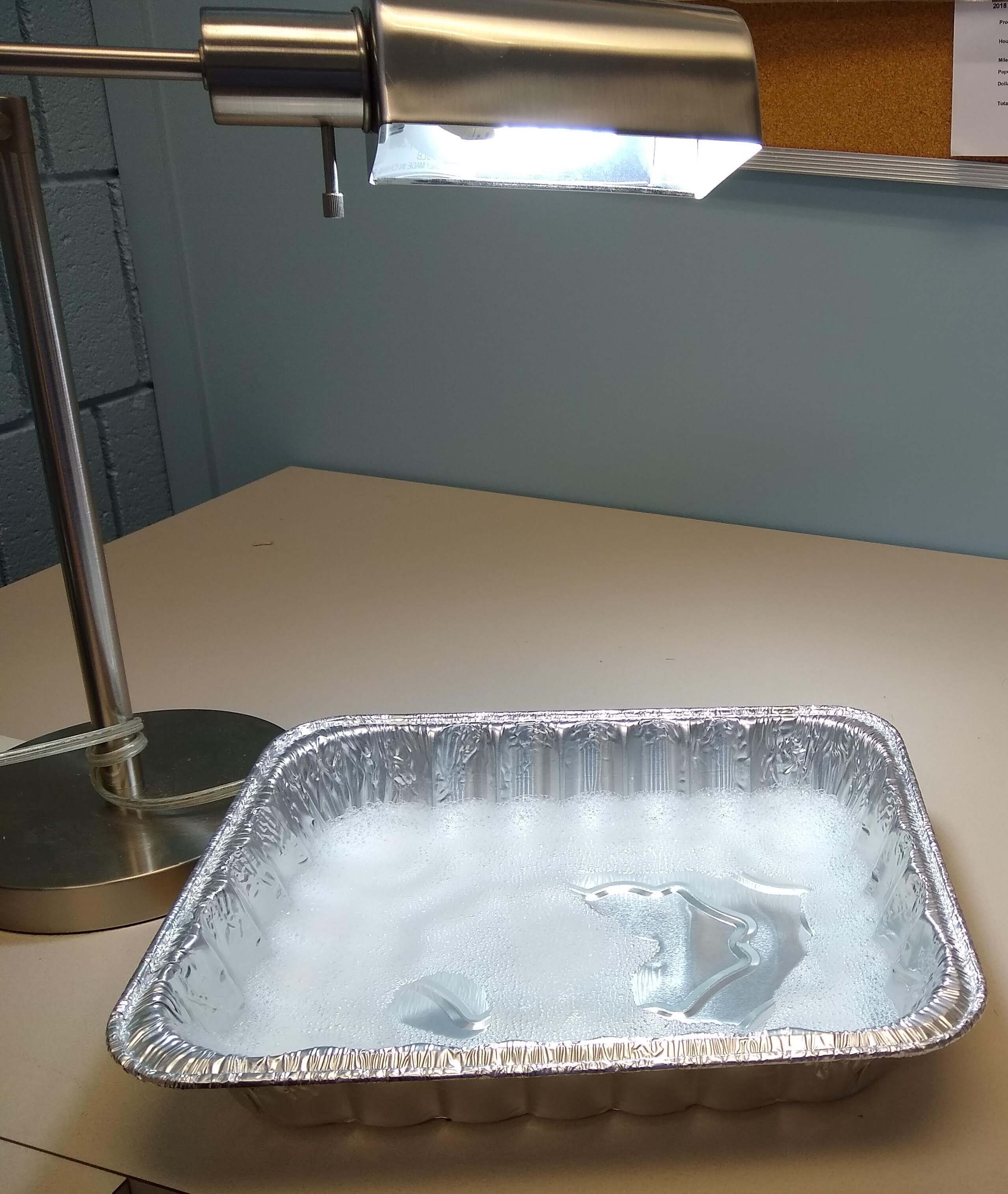

The best way to control indoor nuisance pests is through removal or exclusion. Inside homes, stink bugs are attracted to light and may fly towards light fixtures, resulting in an annoying buzz. A homemade light trap with light shined into a foil pan containing unscented dish soap and water can provide relief at killing stink bugs already inside the home (Photo 3). It is not recommended to apply insecticides to overwintering insects that are already inside your home. The chemicals will only kill insects that make direct contact and will not prevent additional insects from finding their way inside.

When hundreds of stink bugs are found in the home or shed, they can be vacuumed with a shop-vac. On warmer winter days, a stray stink bug or two may emerge from diapause and walk or fly around the house. By this time, all overwintered insects are already inside a home, and hand-picking is the easiest way to eliminate them.

This article was published by Michigan State University Extension. For more information, visit http://www.msue.msu.edu. To have a digest of information delivered straight to your email inbox, visit http://www.msue.msu.edu/newsletters. To contact an expert in your area, visit http://expert.msue.msu.edu, or call 888-MSUE4MI (888-678-3464).